by Neville Teller

On April 18, 2022 Turkey launched a new ground and air offensive against Kurdish militants in northern Iraq. Supported by helicopters and drones, Turkish jets and artillery struck suspected targets of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, and then commando troops crossed into the region by land or were airlifted by helicopters. In short, in a move disturbingly akin to Russian president Vladimir Putin’s in Ukraine, Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan invaded the territory of a sovereign nation – Iraq – in pursuit of a political purpose of his own.

Erdogan is acutely anxious about where political change might be taking the Kurdish nation as a whole, including Turkey’s substantial Kurdish minority. The 14 million Kurds living in Turkey make up 18 percent of Turkey’s population.

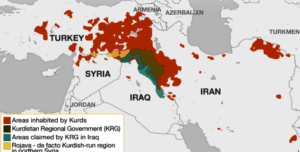

Once upon a time the Kurds were a proud and independent nation thriving in their own land. Subject to many foreign invasions, they refused to be integrated with their various conquerors and retained their distinctive culture. At the start of the First World War, their country, Kurdistan, was a small part of the Ottoman empire. Afterwards, in shaping the future Middle East the Western powers, in particular the UK, promised to act as guarantors of their freedom. It was a promise subsequently broken. Denied independence in their own homeland, the Kurdish people were split largely between four states newly endorsed by the League of Nations. They became minorities in the mountains and valleys of southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northern Syria.

The PKK, founded in 1978, was and is an armed political group. Claiming to represent all people in historically Kurdish regions, it has affiliated itself with other political and social groups including leading political parties in Turkey and Syria. The PKK is also present in Iran, where members fought against the Iranian regime for several years before agreeing to stop military hostilities in 2011.

The PKK’s original objective was to establish a socialist Greater Kurdistan uniting the Kurdish regions of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Iran. Since the mid-2000s, however, there has been a new goal, master-minded by Abdullah Ocalan, the PKK leader imprisoned by Turkey since February 1999 on İmralı island in the Sea of Marmara, where he is serving a life sentence.. Setting to one side the political aim of uniting the Kurdish people in their own homeland, the new objective, dubbed “democratic confederalism”, seeks to establish autonomous Kurdish areas in Iran, Turkey, Syria, and Iraq. Something of the sort now exists in both Syria and Iraq.

Erdogan is unconvinced. He is aware that the idea of an amalgamated Kurdish state, involving a change of national borders, remains a dream among Kurdish extremists, and that conflict within Turkey remains a possibility. The attack on April 18, named Operation Claw Lock, struck shelters, bunkers, caves, tunnels, ammunition depots and headquarters belonging to the PKK, which maintains bases in northern Iraq from where it has attacked Turkey in the past. Turkey’s Defense Ministry said the new offensive was launched after it was determined that the militants were regrouping and preparing for a “large-scale attack.”

Erdogan is also keen to stamp on the idea that disparate Kurdish communities might amalgamate or integrate. This came to the fore during the conflict in Syria against Islamic State. For example, in 2014 Kurdish volunteers from across the Middle East mobilized behind Syrian Kurdish fighters in the battle for the northern Syrian town of Kobane. Syrian Kurds benefited from the fighting experience of the Kurdish commanders who had fought with the PKK in its longstanding conflict against the Turkish state.

Guney Yildiz, a researcher and journalist based in London, focuses on Turkey, the Kurds and Syria. He has advised the UK Parliament’s Foreign Affairs Select Committee on Turkey, worked for BBC News and also the Middle East Institute based in Washington D.C. Yildiz maintains that Kurds across all four nations – Turkey, Iran. Iraq and Syria – are today receiving public and moral support from each other and from the Kurdish diaspora abroad. He believes it is relevant to ask whether Kurds will be content to continue as confederated autonomous areas within nation states, or whether they will seek political independence.

The answer, he believes, lies in how cross-pollination, political recognition, and geography will connect Kurds in Turkey (known to political Kurds as “Northern Kurdistan”), with Kurds in Iraq (known as “Southern Kurdistan”), with Kurds in Iran (“Eastern Kurdistan”), to Kurds in Syria (“Western Kurdistan”).

This is Erdogan’s nightmare scenario. The PKK has been an armed group within Turkey’s body politic for decades, seeking Kurdish independence through acts of terror. As such it was viewed by the Turkish establishment as an existential threat to the state. In 2016 Joe Biden, then US Vice President, confirmed that Washington regarded the PKK as a danger to Turkey’s integrity and, comparing it to Islamic State, said it was “a terror group plain and simple”.

Nothing like unity of policy or purpose reigns within the Kurdish camp as a whole. The Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq has an uneasy relationship with the PKK group, whose presence complicates the region’s lucrative trade ties with Turkey. Erdogan’s Operation Claw Lock was launched two days after a rare visit to Turkey by the prime minister of Iraq’s autonomous Kurdish region, Masrour Barzani, suggesting that he went to be briefed on Ankara’s plans. Barzani said after his talks with the Turkish president that he welcomed “expanding cooperation to promote security and stability” in northern Iraq.

Turkey routinely carries out attacks in the Kurdish region of northern Iraq, where the PKK has bases and training camps in Sinjar and on the mountainous border with Turkey. But the offensives have strained Turkey’s ties with Iraq’s central government in Baghdad.

. Iraq’s President Barham Salih termed the latest incursion “unacceptable”, describing it as a threat to the country’s national security and a violation of its sovereignty. He is certainly not wrong out that.