Uniquely among the 50 Muslim-majority nations of the world, Lebanon has a Christian president. The inauguration of Michel Aoun on 1 November 2016 ended a 29-month power vacuum and a political stalemate that had frozen the country’s constitutional processes.

“Not before time” would be a natural reaction, considering the length of the presidential inter-regnum. The truth, however, is that the absence of a largely figurehead president over that period, while politically inconvenient and somewhat of an embarrassment, made little difference to Lebanon as it ambled along under the guidance of prime minister Tammam Salam.

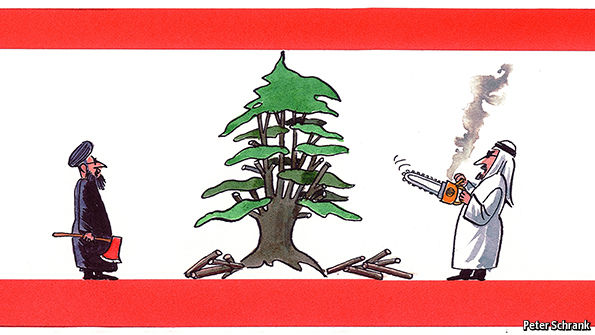

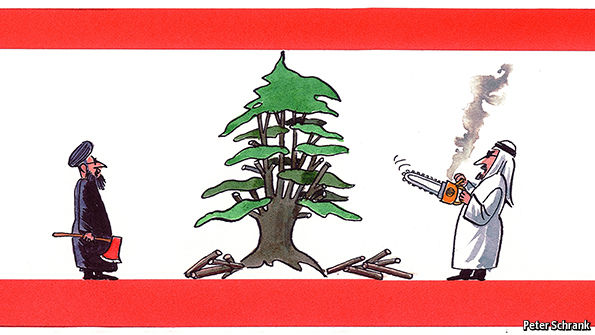

Along the way, Lebanon’s relations with Saudi Arabia plummeted as Hezbollah, an integral part of Lebanon’s body politic, plunged into the Syrian conflict together with Iran’s Revolutionary Guards in support of President Bashar Assad. Aoun took early steps to repair fences by visiting Saudi Arabia in January 2017. He could do little domestically to mitigate the result of an influx of more than a million refugees fleeing the horrors of the civil war that raged in Syria. Lebanon’s population of less than 4 million in 2000 had, by the end of 2016, swollen to more than 6 million, most of the addition being Sunni Muslim refugees.

In theory Lebanon should be a template for a future peaceful Middle East. It is the only Middle East country which, by its very constitution, shares power between Sunni and Sh’ite Muslims and Christians. Theory, however, has had to bow to practical reality. In fact, Lebanon has been highly unstable for much of its existence, and its unique constitution has tended to exacerbate, rather than eliminate, sectarian conflict.

Modern Lebanon was established in 1944 on the basis of an agreed “National Pact”, with the top three positions in the state allocated so that the president is always a Maronite Christian, the prime minister a Sunni Muslim, and the Speaker of the Parliament a Shi’a Muslim.

Theoretically no system could seem more just, more designed to satisfy all parties in a multi-sectarian society. In practical terms, it has proved a constant irritant, and efforts to alter or abolish it have been at the centre of Lebanese politics for decades.

The Taif agreement which ended the Lebanese civil war in 1989 incorporated a deal with the Christian community designed to buy their acceptance of their defeat in the conflict. Based on the fiction that Christians made up half the population of Lebanon, Taif reserved half the seats in parliament for them. Everyone knew that the parliamentary allocation was unfair. A recent analysis of voter registration lists by The Economist revealed that only 37% of Lebanese voters are Christian; Shias are 29 percent; Sunnis, 28 percent. Yet the Christians get 64 of parliament’s 128 seats, whereas the Sunnis and Shias get only 27 each, the rest going to the Druze and Alawites. Meanwhile, not only the Syrian refugees, but also the half-million Palestinians, most of them Sunnis, who have arrived in Lebanon since 1948, have never been granted citizenship and are debarred from voting..

This mismatch between demography and political power partly explains the presence of Hezbollah in the Lebanese government.

Hezbollah, an extremist Shia Islamist group, emerged in the early 1980s as an Iranian-sponsored movement aimed at resisting the presence of Western and Israeli forces. Responsible for a string of notorious terrorist actions, such as the suicide car bombing of the US embassy in Beirut in April 1983, and the blowing up of the United States Marine barracks six months later, Hezbollah was born in blood, fire and explosion.

It can scarcely be said to have become respectable, but Hezbollah achieved a certain acceptability in Lebanese society following Israel’s withdrawal in May 2000 from the buffer zone it had established along the border. In the election that followed Hezbollah, in alliance with Amal, took all 23 South Lebanon seats out of a total 128 parliamentary seats. Since then Hezbollah has participated in Lebanon’s parliamentary process and been able to claim a proportion of cabinet posts in each government. As a result it has achieved substantial power within Lebanon’s body politic – far too much, according to the March 14 Alliance, an organization dedicated to overthrowing this “state within a state”. Now, although the new prime minister, Saeed Hariri, is a long-time opponent of Hezbollah, it has secured two ministerial posts.

Liberating Lebanon from the influence of Hezbollah and Syria was the aim of Saeed’s father, former prime minister Rafik Hariri, who was assassinated in February 2005. When then UN Secretary General, Kofi Annan, sent a fact-finding mission to Beirut to discover who was responsible, he was certainly unaware that he was giving birth to what might be termed a new judicial industry – the Lebanon Inquiry process. Now in its twelfth year it is being conducted by the Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL) which, if its elaborate website is anything to go by, is comparable to some thriving commercial enterprise.

The STL court, consisting of 11 judges, sits in The Hague. So far no less than 236 witnesses have provided testimony, 113 of them in person. Hearings are broadcast through the STL website. The tribunal runs its own public affairs office, which arranges briefings and interviews for journalists, and a media center whose facilities include Wi-Fi internet access, television screens to follow the hearings, and recording facilities in Arabic, English and French.

Ever since Hariri’s assassination, Hezbollah and the Syrian régime have sought to disrupt the UN investigation. As a result the five identified defendants have not been apprehended, and the trial of Ayyash et al. is being held in absentia. When it began on 16 January 2014, after years of pre-trial hearings, the prosecution carefully steered clear of accusations against Syria. Latterly it has become clear that the prosecution believes President Bashar Assad wanted Rafik Hariri killed, and used Hezbollah and his own security apparatus to achieve his objective. Hearings are scheduled to continue well into 2017, and possibly beyond, but Assad and Hezbollah face an increasingly probable verdict of having planned and executed the murder of Rafik Hariri.

On 17 January Michel Aoun visited the Special Tribunal for Lebanon for a briefing by the two leading judges. Judge Ivana Hrdličková is reported as telling Lebanon’s new president: “I am determined to promote the values of efficiency, transparency and accountability”. She said nothing about when the interminable judicial process might reach a conclusion. But when it does, will Lebanon be prepared for the political consequences?