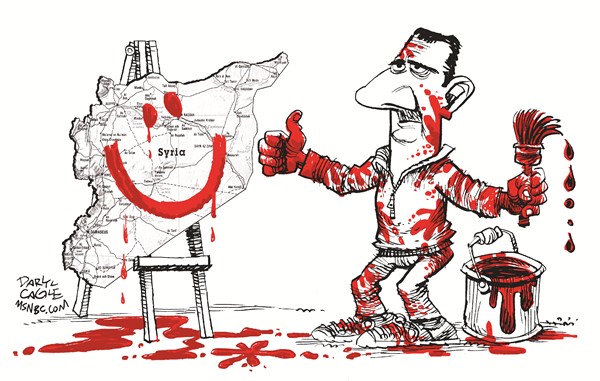

Back in the glory days of the so-called “Arab Spring”, when Middle Eastern dictators were falling like ninepins, it seemed that the overthrow of Ben Ali of Tunisia, Mubarak of Egypt, Gaddafi of Libya and Saleh of Yemen would inevitably be followed by the downfall of President Bashar Assad of Syria.

But, it now seems, providence had reserved a different fate for Assad. A determination to cling to power, however ruthless or inhumane the methods, allied to a favourable concatenation of political circumstances, has enabled Assad to emerge from a long, multi-faceted combat battered, depleted territorially and logistically, but still in power.

[one_half padding=”0 10px 0 0″][starbox][/one_half]

In the amoral world of international relations, power commands respect. So it is, perhaps, not surprising that green shoots of acceptance are beginning to sprout, even among states that were once totally opposed to Assad.

From the beginning Assad found himself with powerful allies to help counter his formidable opponents. Syria has long been a vital component of Iran’s so-called “Shia crescent” (so dubbed by Jordan’s King Abdullah) – that area of Shia and Shia-allied states and peoples that form the foundation of Iran’s policy for achieving religious, and thus political, hegemony in the Middle East. The crescent embraces Lebanon and so, in supporting Assad against the Syrian democratic forces that were attempting to overthrow him, Iran was able to augment its own Revolutionary Guards with Hezbollah fighters.

Dictators take risks, often winning a trick by relying on the spinelessness of their opponents. Assad knew full well that US President Obama had threatened immediate counter measures if chemical weapons were used in the Syrian conflict. Nevertheless, sensing indecision in his opponent, in August 2013 Assad authorised the use of the potent nerve agent, sarin, in an attack on the town of Ghouta, quite regardless of collateral civilian casualties. Sarin is officially designated a weapon of mass destruction.

In the event Obama turned somersaults to avoid the decisive response he had promised. When Russia’s President Putin claimed to have extracted an undertaking from Assad to destroy all the chemical weapons he had originally claimed not to possess, Obama seized on the chance of avoiding any form of punitive action. The result was enormously to strengthen Putin’s position in the Middle East, while the deal was not worth the paper it was written on – if indeed it was ever written down. The subsequent record abounds with convincing evidence of the continued use by Assad of chemical weaponry of various kinds, including VX, sulphur mustard and chlorine.

Meanwhile Assad had assured himself of a powerful new ally in his effort to cling to power in Syria. For his part Putin had two main objectives in view when he sent his forces into Syria on September 30, 2015 – to establish Russia as a potent political and military force in the region, and to secure his hold on the Russian naval base at Tartus and the refurbished air base and intelligence-gathering centre at Latakia. He achieved both, as he launched massive air and missile attacks mainly against Assad’s domestic enemies, namely the rebel forces led by the Free Syrian Army (FSA).

As a result, by the end of 2016 Assad had retaken the city of Aleppo after a particularly brutal conflict, and in addition currently controls the capital, Damascus, parts of southern Syria including the tiny enclave of Deir Az Zor in the south-east, much of the area near the Syrian-Lebanese border, and the north-western coastal region.

Nothing succeeds like success, and some of the states in the Middle East are reported to be making tentative moves towards a rapprochement with Assad.

Jordan’s position towards the Syrian civil war has never been entirely clear. While supporting moderate rebel groups from the FSA, the Jordanians have not openly called for Assad to step down, and recent reports seem to indicate that Jordan is moving closer to him and his supporters. It was at Russia’s invitation that Jordan attended the latest round of talks between the Syrian regime and rebels in Astana. It was also present during the Geneva talks on 23 February 2017. In addition Jordan’s King Abdullah recently met with Lebanese President Michel Aoun, a staunch supporter of Assad, to discuss the Syrian crisis.

Jordan is hosting the Arab League annual meeting scheduled for 29 March. Syria was suspended from the League in 2011 over Assad’s failure to end the bloodshed caused by brutal government crackdowns on pro-democracy protests, and the League imposed economic and political sanctions on him. So, as was the case in previous summits, Assad was not invited to the forthcoming meeting.

And yet recently reports have begun to emerge of a concerted attempt by Russia, Egypt and Jordan to get Assad readmitted to the League. This move was apparently spearheaded on 25 February by Egypt’s parliamentary Committee for Arab affairs, which issued a statement describing Syria’s continued suspension as totally ‘unacceptable’.

A response from the Syrian side was not long in coming. Botros Morjana, head of the Arab and Foreign Affairs Committee at Syria’s People’s Assembly, expressed the committee’s appreciation of the call for the return of Syria to the Arab League.

There is as yet no indication that Assad will indeed be attending the forthcoming meeting. Rumours however abound: there’s been a flurry of official and diplomatic activity; military officers and intelligence agents from Russia, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and Syria have been flying back and forth between Cairo, Riyadh, Amman, Damascus and the Russian command in Syria, all engaged in detailed planning for the event; Assad will arrive in Amman armed with a Russian safe-conduct guarantee, aboard a Russian military aircraft which would fly him there and back from Russia’s Syrian air base at Hmeimim. And so forth.

If Putin could indeed persuade Saudi King Salman to accept Assad’s return to the Arab summit, the Russian president’s reputation in the Arab world would soar. An historic handshake and greetings between Assad and Salman would signify the reconciliation between Saudi Arabia, which backed the Syrian rebels, and the Assad regime. But for Assad, whom few expected to emerge alive from the nearly seven years of warfare, it would mark collective Arab recognition of his personal triumph against all the odds. It may not happen this time – but it’s on the cards.