by Neville Teller

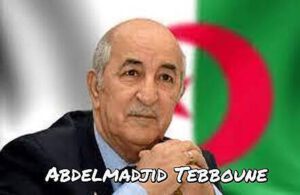

In an effort to heal the long-lasting rift between the two main Palestinian political bodies, Fatah and Hamas, Algeria’s president, Abdelmadjid Tebboune, announced on December 8, 2021 that he planned to host a meeting of Palestinian political organizations.

A Hamas spokesman told the media that Hamas was keen to attend the conference and benefit from the Algerians who “stand at the same distance” from all the Palestinian factions.

Preparations for the conference have gone ahead, although at the time of writing an actual date had yet to be announced. Four Palestinian bodies have been invited in addition to Fatah and Hamas, namely Islamic Jihad, PFLP (the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine), DFLP (the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine), and PFLP-GC (the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command).

By January 17 delegations from all six had arrived in Algiers for preliminary talks with officials.

They face a hitherto insurmountable problem, for a fault line runs straight down the middle of Palestinian politics. The problem is exemplified by the feud between Hamas and Fatah. The struggle between them is not concerned with political objectives. Both bodies aspire to restore the whole of historic Mandate Palestine to Islamic rule. Their fundamental disagreement is over the strategy for achieving their common purpose.

The Hamas organization – a sprig of the Muslim Brotherhood – came into being in 1987, soon after the start of the first intifada masterminded by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) under its Fatah leader Yasser Arafat. Hamas regarded the PLO in general, and Arafat in particular, with a good deal of suspicion. It strongly opposed the PLO entering peace talks with Israel, and it utterly rejected the Oslo Accord agreements of 1993 and 1995, condemning Arafat outright.

Hamas has no truck with the two-state solution. It has opposed all the efforts by Palestinian Authority (PA) President Mahmoud Abbas to gain international recognition for a state of Palestine comprising the West Bank, Gaza and East Jerusalem. Delineating a sovereign Palestine on only part of Mandate Palestine would inevitably legitimize Israel’s place on the other part.

While this fundamental difference about the most effective route to reach their common objective lies at the heart of the Hamas-Fatah conflict, there are others. Both bodies are engaged in a battle for the hearts and minds of the Palestinian population, and Hamas makes no secret of its aspiration to replace Fatah as the governing body of the West Bank. Sometimes it chooses to acknowledge Abbas as Palestinian leader; sometimes it refuses to recognize him as PA president at all, on the grounds that his presidential mandate, granted in 2005, was for a four-year term which has long expired. Hamas has, moreover, consistently attempted to undermine his PA administration by forming militant cells in the West Bank aimed at launching attacks on Israel.

With such fundamental differences on open display, sympathetic world leaders have attempted time and again to broker a reconciliation between Hamas and Fatah. Wikipedia lists no less than 14 attempts since 2005 to reconcile the two warring factions. All have proved unsuccessful.

Perhaps the most hopeful was the “government of national unity” formed by agreement between Fatah and Hamas in 2014. It brought the peace negotiations then in progress between Israel and the PA to a shuddering halt.

Abbas announced the “historic reconciliation” a month before the talks were due to end, and appeared to imply that the inclusion of Hamas in a government of national unity would make no difference to the aim of achieving a sovereign state based on the two-state solution. But it was inconceivable that Hamas would sit round a cabinet table, with Abbas at its head, and agree to discuss how a sovereign Palestine might live side by side with an Israel finally recognized as a permanent presence in the region.

National unity lasted just twelve months. Nationwide Palestinian elections, promised as part of the deal, never took place.

The failure to deliver promised elections was also the issue that scuppered the most recent reconciliation effort. Then-President Trump’s Israel-Palestine peace plan, launched in January 2020, met with universal disapproval on the Palestinian side. Abbas decided to coordinate the PA’s struggle against the plan with Hamas. In September 2020, Abbas held a joint press conference with Hamas leaders, confirming a new dialog aimed at reconciliation. Presidential and parliamentary elections leading to a unity government were announced for May 2021.

Just days before they were due to take place, Abbas issued a presidential decree postponing them, claiming that his decision was due to an Israeli ban on Jerusalemites taking part in the polls. Some claimed it was because Hamas was likely to win the elections, or at least gain a substantial number of seats. Hamas condemned the postponement, and hit back with armed attacks and a bid for recognition as the true Palestinian champions.

Against a background like this, the chances of the Algerian initiative yielding anything approaching a lasting reconciliation seem slim. Yet there is a new factor at play. The Abraham Accords demonstrate a recognition in the moderate Arab world of the benefits of normalization with Israel. A new Middle East is emerging, and the Palestinian issue is slipping down the world’s agenda. With every passing year the hopes of those who would overthrow the State of Israel recede further into the realms of fantasy.

The Algerians have opened the doors of a last chance saloon. Can the hardline extremists within Hamas and the other Palestinian factions reconcile themselves – even with their fingers crossed and their private aspirations undimmed – to uniting with Fatah in seeking a realistic accommodation with Israel?

The writer is Middle East correspondent for Eurasia Review. His latest book is: “Trump and the Holy Land: 2016-2020”. Follow him at: www.a-mid-east-journal.blogspot.com