by Neville Teller

An unexpected piece of news broke just as the 14-day international COP26 conference on climate change drew to a close. The host for COP27 in 2022 is to be Egypt. Moreover, in the interim, Egypt partnered by the Maldives is to organize workshops to boost international adherence to the commitments made at COP26.

COP27 is to be held in the Red Sea resort of Sharm El-Sheikh on the south-eastern edge of the Sinai peninsula. Egypt’s president, Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, in making his bid to host it, said that Egypt would work to make it “a radical turning point in international climate efforts in coordination with all parties, for the benefit of Africa and the entire world.”

The fact that Egypt is about to assume a major role in a key area of international policy is a testament to Sisi’s determination. The path toward international recognition of Egypt as a leading player on the world stage has not been without its difficulties. To succeed Sisi needed to mend fences with the Biden administration.

Then-US President Barack Obama had disapproved of Sisi’s coup against Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood president Mohamed Morsi, and condemned Sisi’s crackdown on opponents of his new regime. Joe Biden, Obama’s vice-president throughout his two terms, made it clear from the start of his own presidency that he was going to hassle Sisi on his human rights record.

“We will bring our values with us into every relationship that we have across the globe,” said State Department spokesman Ned Price in March 2021. “That includes with Egypt.”

Sisi knew that a vital step in his bid for enhanced global recognition was to persuade Washington to resume the regular program of US-Egypt strategic discussions. This series of dialogues was established under the Clinton administration in 1998 and held periodically since then, apart from a gap from 2009-2015 starting with the Obama administration.

Sisi pulled it off. On November 8 US Secretary of State Antony Blinken participated in the opening session of the revived US-Egypt dialogue. Afterward Egypt’s foreign minister, Sameh Shoukry, declared that the talks had boosted relations between the two countries and been a great success.

In warming US relations with Egypt, Biden is not without his critics. Human Rights Watch (HRW) has long condemned Sisi’s ruthless suppression of opposition to his government, an opinion widely shared within the Democrat party. Aware of this, early in September Sisi issued what he termed his “National Strategy for Human Rights 2021-2026”. Nominally an effort to establish a new strategy for human rights in Egypt, Sisi called it a milestone in the country’s history. Reporting on the announcement, though, journalists and civil rights supporters were highly skeptical. They await action in support of the fine words, and they may yet get it.

On October 25, making a move in the right direction, Sisi lifted the state of emergency he had imposed on the nation more than four years ago. Once again HRW, while welcoming the move, declared it far from sufficient to deal with what it terms “the country’s prolonged human rights crisis”.

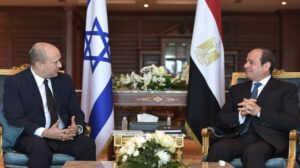

The groundwork for Sisi’s re-engagement with Washington had been laid months before. In September he traveled to Sharm el-Sheikh to meet with Israel’s newly elected prime minister, Naftali Bennett.

Afterward Bennett said the two leaders had “laid the foundation for deep ties moving forward.” He told reporters that the talks covered diplomacy, security and the economy, including aspirations to expand trade and tourism. Other sources disclosed that the discussion had also addressed regional issues, including Iran’s nuclear program and Sisi’s aspirations for a resumption of the Israel-Palestinian peace process, based on the presumption of a two-state solution.

No doubt Sisi arranged this open show of friendship toward Israel with one eye on Washington, and subsequent events showed that the move was astute. The warm meeting with Israel’s prime minister was a way of Sisi reminding the US that Egypt is an irreplaceable player in maintaining stability in the Middle East – a point included in the joint statement that followed the US-Egypt strategic dialogue.

Sisi has proved his value to US interests in a number of ways. The 11-day conflict between Hamas and Israel in May was resolved as a result of Egypt acting as honest broker – an outcome not originally foreseen by Washington. Subsequently Sisi placed himself in a key role in the Gaza situation by facilitating discussions between the main players – Hamas, Israel and Qatar – the outcome of which is still in the balance. Following the meeting with Sisi, Bennett’s office mentioned Egypt’s role in maintaining stability and calm in Gaza.

The Israeli and Egyptian military have been cooperating for years in northern Sinai against jihadist forces intent on undermining Sisi’s anti-Muslin Brotherhood administration. On November 8 the Israel Defense Forces announced that the Egyptian army was to step up its activities in the Rafah area in north-eastern Egypt. The decision had been taken at a meeting of the joint military committee of the Israeli and Egyptian armies. The army statement said the move “was approved by the Israeli political echelon.”

The 1979 peace treaty between Egypt and Israel stipulated that agreed security arrangements were to be established, and that, upon the request of either of the parties, the security arrangements could be modified.

More broadly, US disengagement from the Middle East under Biden has spurred Sisi into seeking meaningful relationships with China and Russia. Sisi has given both world powers lucrative contracts. China, by way of the China State Construction Engineering Corporation (CSCEC), is building Egypt’s new administrative capital city, some 28 miles east of Cairo, on a vast plot of desert equal to the size of Singapore. In August Egyptian delegations visited nuclear power plants in Russia in order to finalize a deal connected with the construction by Russian nuclear power producer, Rosatom, of Egypt’s first nuclear reactor at El-Dabaa.

In both cases, and in other deals with these leading powers, Sisi has taken particular care not to jeopardize Egypt’s deep and, it seems, growing relationship with the US. His aim is to enhance Egypt’s standing, and his own, in the world. Given the visit of Prince Charles, heir to the British throne, and his wife on November 17, he seems to be succeeding.

The writer is Middle East correspondent for Eurasia Review. His latest book is: “Trump and the Holy Land: 2016-2020”. Follow him at: www.a-mid-east-journal.blogspot.com