by Neville Teller

At present Israel is in a rather equivocal position on the African political scene. The issue cannot be resolved until 2023.

The problem revolves around the African Union (AU), which came into existence in 2002 replacing the rather ineffective Organization of African Unity (OAU), founded in 1963. Israel, having built up cooperative relationships with dozens of African states over the years, had been granted observer status in the OAU. When the African Union was set up, though, Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi took the lead in persuading members to deny Israel its previous observer status.

Since then Israel has tried several times to regain its old position, its efforts consistently frustrated by a group of members led by South Africa. Finally Israeli diplomacy triumphed. On July 22, 2021 the Chair of the AU Commission, Moussa Faki Mahamat, announced that Israel would be admitted to the African Union as an observer state.

Faki’s decision, however, was not the end of the matter. A number of members, including the Palestinians, who have enjoyed observer status in the AU for some years, objected on the grounds that the matter had not been put to the vote. Several countries, led by South Africa and Algeria, began lobbying members in the hope of reversing the decision, and this group decided to seek a general vote at the annual AU summit in Addis Ababa in February 2022.

In a communiqué justifying his action, Faki pointed out that in granting Israel observer status he had acted entirely within the discretion granted him under the criteria establishing his office. Moreover, he said his decision had been “taken on the basis of the recognition of Israel, and the reestablishment of diplomatic relations with Israel, by a majority greater than two-thirds of AU member states, and at the expressed request of many of those states.” In fact, only eleven AU members out of the 54 did not have full relations with Israel, and of those eleven, several enjoy various agreements or understandings with Israel.

The issue was indeed placed on the agenda of the 2022 AU summit, but the plan to persuade members to overturn Faki’s decision was frustrated when the newly elected Chair of the AU, Senegalese President Macky Sall, suspended the debate, later announcing that a special committee would be set up to deal with the issue. “It will be composed of eight heads of state and governments,” he said, “and will present its recommendations at the next summit.” Along with South Africa and Algeria, the committee will include Rwanda, Cameroon, Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the next summit is scheduled for early 2023.

The foreign policy strategy most closely connected with Israel’s first prime minister, David Ben Gurion, has become known as the Alliance of the Periphery. It called for Israel to develop close strategic alliances with non-Arab Muslim states in order to counteract the then united opposition of Arab states to Israel’s very existence.

Pursuing it, successive Israeli governments achieved a working relationship with a number of nations like the newly-independent Muslim republics of Central Asia such as Kazakhstan and Tajikistan. Relationships were forged also with African states like Ethiopia and Nigeria.

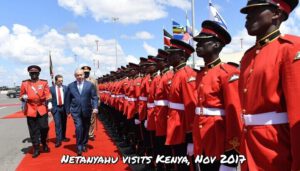

As prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu set about applying a renewed version of the Periphery Doctrine inside continental Africa, by-passing the apparently hopeless case of South Africa. On July 4, 2016 Netanyahu landed in Uganda on a five-day. four-country trip inside the continent, also visiting Kenya, Rwanda and Ethiopia. He was accompanied by approximately 80 businesspeople from over 50 Israeli companies to help forge new commercial ties with African companies and countries.

In Uganda an official ceremony was held at Entebbe to mark 40 years since the daring raid by Israeli commandos to release hostages held captive by then-President Idi Amin. Netanyahu then participated in an Israel-Kenya economic forum along with businessmen from both countries, dealing with issues like agriculture, water resources, communications and security. Later the leaders of seven East African states (Uganda, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Zambia and Tanzania) sat round a table with Netanyahu to discuss how to enhance cooperation with Israel in cyber defense, energy, agriculture, trade, diplomatic and related matters. To sweeten the discussion, Netanyahu was able to put on the table a financial assistance package of 50 million shekels ($13 million), approved by the Israeli government the previous week.

The following year Netanyahu visited Liberia to address the 15-member countries of the Economic Community of West African States – the first non-African head of state to do so. He appealed for political support in return for economic aid and technical assistance in sectors such as agriculture, water resources, energy and health. He also lobbied for African Union observer status.

More recently Israel has made inroads in North Africa too. In 2019 it re-established relations with Chad, broken off in 1972. Faki, the AU Commission chair, comes from Chad. Israel also has normalized relations with Morocco and Sudan through the Abraham Accords. Unfortunately the deal that secured Morocco’s acceptance of normalization with Israel created an enemy in Algeria. Then-US President Donald Trump recognized Morocco’s sovereignty over Western Sahara which Algeria, along with the African Union, regards as an independent state, and its people as entitled to self-determination.

Thanks to the efforts of Israeli governments over the years, and of Netanyahu as prime minister in particular, Israel has established deep, strong and effective relationships with most of the member states of the African Union. Yet almost all, friend or foe, are also supportive of the Palestinian aim to achieve an independent, sovereign state – the two-state solution. The Abraham Accords prove that normalization with Israel is not incompatible with supporting Palestinian aspirations. When it comes to the vote, will the members of the AU take the same position?