Labelling 381 million people from 22 countries as monolithic ‘Arabs’ is misleading and inaccurate.

With conflicts raging on in Syria, Palestine, Yemen and Iraq and a diaphanous calm in the rest of the Middle East, the language we use in covering this region is not only hindering our understanding of the issues, but it is also misguiding strategic policies.

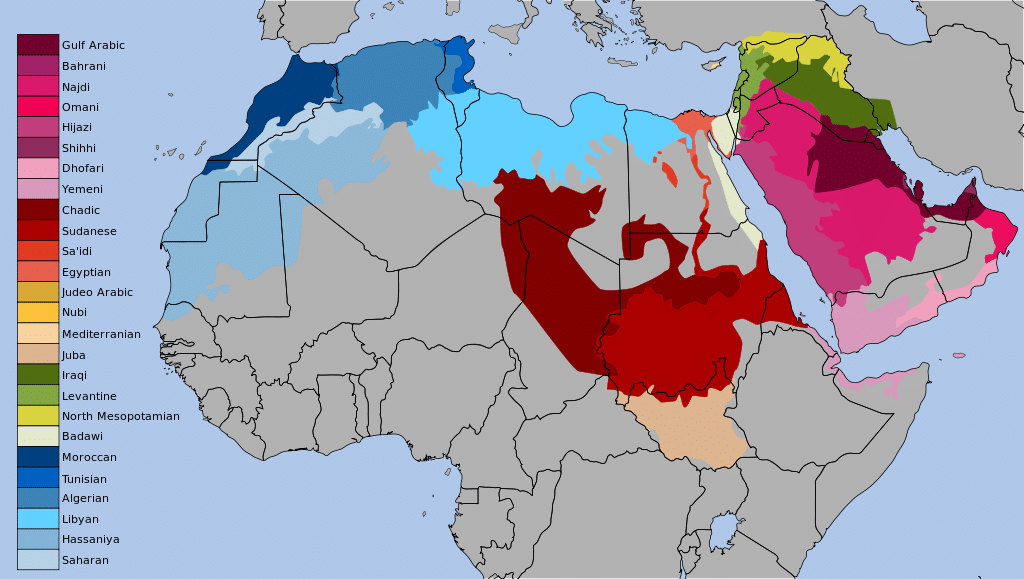

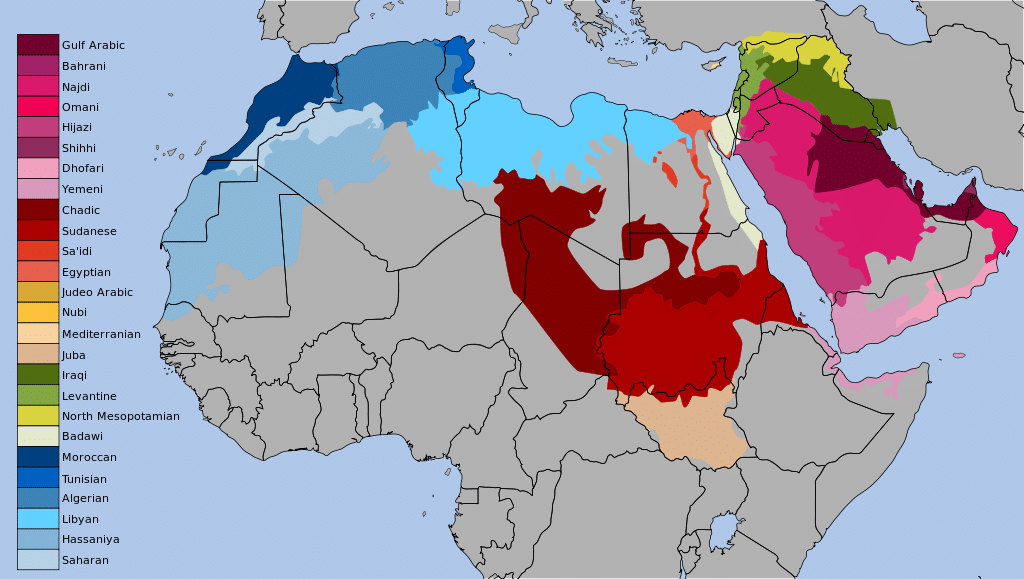

As a journalist covering international events, I have witnessed the narrative covering the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) recede to a thin crescent of one pan-ethnic group, primarily because they speak a dialect of Arabic. At the last count, 35 dialects of the Arabic language are spoken across the two regions.

In a recent discussion one person, referring to Iranians, used the term “Arab speakers”. I wanted to ask whether they were Dolby Digital or Stereo. Instead I pointed out that Iran’s language is Farsi.

The BBC has an “Arab affairs” editor and it is not alone. Fellow journalists who are “internationalists” themselves make that mistake; politicians, commentators and academics as well.

This language does nothing to inform and only perpetuates a phantom identity of “Arabs” and the “Arab world”. Both terms are widely used as blanket coverage of the populace in the MENA that displaces the indigeneity of “Arab” into a single basket that mashes 22 countries with a population of 381 million.

Perhaps it is the globalisation of things that has made it acceptable to do away with the specifics of identity? A Google Books search suggests the usage of these terms has shot up to almost 400% since the 1800s.

The MENA consist of many countries and each speaks its own form of Arabic patois, a clear indication of their nationality. Arabic in North Africa is almost incomprehensible to an Arabic speaker from the Levant such as Lebanon. In the case of Lebanon, their version is what I call frou-frou Arabic due to lasting French influences. Lebanon’s native language was Phoenician or Canaan, which was also spoken in coastal Syria, northern coastal Israel and Cyprus. Syria’s once native language that it shared with Iraq and Iran was Assyrian. The Egyptians spoke Coptic. The list goes on.

During an assignment in Israel and Palestine, my Arabic dialect clearly defined my roots from the local Palestinians. The dialects differed wildly when I was in Egypt and even greater when dealing with Iraqis and Libyans. Not to mention cultural differences. As a Lebanese-Australian who lived in Libya as a child and then later worked for the Nine Network Australia during a Gulf war assignment in Saudi Arabia, I found both countries terrifying. They and their lifestyle were alien to me. Yet in this instance, the global membership I had been assigned, told me I belong to others. An otherness dictated by passers-by.

Lebanese biologist, Dr Pierre Zalloua, whose wide body of work includes the National Geographic’s Genographic project – an ambitious worldwide genetic mapping of human history – has a huge interest in this topic and has dedicated a lot of his work to deconstructing the misleading current definitions of identities in general. Zalloua says, “DNA is the most powerful tool that eradicated the word race and embraced the word ethnic background. It does not define or determine an identity, or culture or an ethnicity, it uncovers stories from our past but does not reveal who we really are.”

In my initial contact with Zalloua for this story he cautioned that: “This is a very complex and convoluted topic, very politically charged. One has to have the courage to tackle and be truthful to the facts without prejudice.”

And he was right. In researching for meanings, definitions and categorisations of the term or the regions, there are no definitive answers to populations, countries, sects and languages that accurately agree on what constitutes the MENA. There is no getting away from that ethnocentric mindset that mash-up countries, ethnicities, religions, cultures and languages by referring to the regions, not as the Arabic speaking world, not as the Middle East or North Africa, but as “Arabs” and the “Arab world.” We wouldn’t refer to Scotland, Ireland, Australia, Canada and the USA as “English” or the “English world” but most likely, the English-speaking world.

Robert Hoyland, a professor of archaeology and history at NYU, spent considerable time in Syria and Yemen until the wars started and now teaches at NYU in Dubai. He says that the first reference to the term “Arab” was in 834BC in the Bible and “the race existed in Syria below Palmyra and top of Saudi Arabia, i.e., in the desert between them.”

Before the regions were invaded by the “Arabs” from down south in the Arabian Peninsula, there were existing civilisations. The march north and conquest began in the mid-6th century, across the Persian and Byzantine territories and it was to spread the faith – Islam which was rooted in the Arabic language – not their ethnicity.

The word “Arab” means “nomad” in one camp, in another it is derived from “pure or mixed”. Arabic originated from nomadic tribes in the desert regions of the Arabian Peninsula. The language comes from Nabataean Aramaic script and has been used since the 4th century classical era belonging to the “Semitic” group of languages of Hebrew and Aramaic.

By the 8th century CE, the Arabic language began spreading throughout the MENA, as many people converted to Islam, and were obliged to pray in Arabic. This brings us to the most important constituent in the term “Arab”, i.e. the Arabic language – not people. To describe everyone who is Muslim or speaks Arabic as Arab is incorrect. Religiosity is not ethnicity and nor are they interchangeable.

A lot of what has happened in the MENA is sadly a case of unintended consequences. The struggles in these regions to a great extent has shifted from a nationalist to a religious front, which has led to the interchangeable terms of “Arabs” and “Muslims”. This has been a predominantly western perception, however, and the labelling of “Arabs” as monolithic can only be described as a fear-mongering term to reflect the “war on terror”.

Nonetheless, local contribution via geopolitics and strategic convenience cannot be ignored. Hoyland explains that the term “Arab” is a modern 19th century reference used to break away from the Ottoman Empire as well as Turkish nationalism. After that, the term was embedded with the initiation of the Arab League, specifically Saudi Arabia. It served Saudi very well to cast the one noun to describe two regions because ultimately, as the birthplace of Islam and “Arab”, it was convenient and strategic for this perception to continue. The greater the number of people, the bigger the area, the greater the leverage – and a desperate attempt to hold on to the pan-Islamism and pan-Arabism of yesteryear. The term stuck and was later advanced by Gamal Abed Al Nasser in 1950s and 60s.

But no greater significance did it play until the 1967 war with Israel to give the perception of a big military force – a phantom bigness. Nowadays, the same term is a convenience for hawkish Israelis to refer to the Palestinians, casting them into that otherness, further into a phantasmagorical horror, and to erase their identity from lexicon listings.

According to Hoyland, the “Arab” term is becoming less popular in the Middle East, because the movement is seen as “backward”. “Nationalism and Islam has had its day,” he says.

Last year, the US Census Bureau held a forum to improve classifications of nationalities, race and ethnicities of the MENA, inviting 40 experts to discuss current data. The outcome of the forum will most likely lead to an increase in the number of classifications of ethnicities, race and nationalities in the MENA. This may get us closer to a more concise representation of the realities, rather than assumptions, and may help us understand the complexities of the regions. In lands of millions of Arabic speakers, not everyone is Ali or Abdullah nor Sunni or Shia. Islam consists of a significant number of branches and sub-branches (26 at last count), as well as non-Muslims.

“The question is not really whether it is correct but whether it is useful,” Hoyland says. “It is not correct in the sense that everyone that lives in this region is an Arab or wants to be referred to as Arab.”

We need to scrap the free memberships that misplace ethnicity, identity, culture and history. Doing so would not only go some way to preventing exclusion, but also give context, and provide a starting point in promoting understanding. It may even prevent incidents of racism and bias towards anyone or anything that comes from the Middle East and North Africa and happens to speak a dialect of Arabic.

Source: The Guardian