by Neville Teller

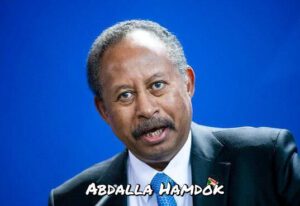

Abdalla Hamdok’s career as Sudan’s prime minister is a roller-coaster of a story. 66-year-old Hamdok, who holds a doctorate in economics from Britain’s Manchester University, was a well-respected technocrat when, following the overthrow in April 2019 of Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir, he was called on to lead the government. An agreement had been reached between the civilian element within Sudan, the Forces for Freedom and Change (FFC), which had pressed for change, and the army, which engineered the coup. The country was to be governed by a coalition of military and civilian powers who pledged themselves to move the country toward democracy and parliamentary elections in 2023.

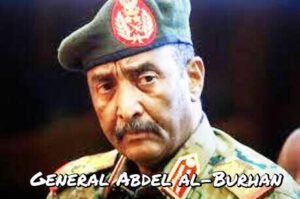

The military arm was led by General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, who was also the head of the overriding administrative body, Sudan’s Sovereign Council. The arrangement was unstable. Popular feeling grew increasingly impatient with the leadership’s failure to deal with the country’s severe economic problems and the obvious lack of progress toward any form of democracy. On October 22, 2021 national frustration erupted in a mass protest in the capital, Khartoum, estimated at a million strong, in support of full civilian rule.

Three days later Burhan dissolved the country’s civilian cabinet, arrested prime minister Hamdok and other leading figures, and declared that the country was under military governance. Hamdok was out.

Any hopes Burhan may have cherished of quickly consolidating his seizure of power were soon shattered. He was faced with instant and near-universal condemnation. The UN, the African Union, the Arab League and Sudan’s Western donors – including the US – all called for the return of Sudan to civilian rule. Within the country, popular opposition to the military takeover rose to boiling point.

Burhan began to pull back. On November 4 he spoke on the phone with US Secretary of State, Anthony Blinken. “The two parties agreed on the need to maintain the path of democratic transition,” said Burhan’s office immediately afterward. Burhan then ordered the release of Hamdok and other government ministers he had deposed in the coup, and opened negotiations with them.

On November 21 a 14-point political agreement was signed, enabling Hamdok to be reinstated as prime minister. It also provided for the release of all political prisoners detained during the coup, and laid down the requirements for the transition of the country to democracy and full civilian rule. Elections were to be held in July 2023. “We will continue to work toward preserving the transitional period until all your dreams of democracy, peace and justice are achieved,” said al-Burhan. after Hamdok’s recall to office.

It lasted just six weeks. Late on Sunday, January 2, Hamdok appeared on state television to announce his resignation as Sudan’s prime minister. Reports indicated that he objected to Burhan’s refusal to allow him to appoint his own cabinet, and opposed Burhan’s decision, announced on December 30, to restore former dictator Omar al-Bashir’s notorious national intelligence service (NISS). now to be known as the General Intelligence Service (GIS). In any case the pro-democracy movement had regarded Hamdok’s return as a fig-leaf to legitimize the coup and ensure the military’s dominance.

With Hamdok gone, analysts say the military may look to co-opt a new civilian face to retrieve billions of dollars in much-needed foreign aid, which was suspended following the coup.

One name being mentioned is Ibrahim Elbadawi, a former finance minister who served under Hamdok in 2019, but Burhan has been warned off simply imposing their nominee. The US, the EU, the UK and Norway have threatened to withhold financial assistance if “a broad range of civilian stakeholders” was not involved in the process.

Meanwhile popular protests have shown no sign of slowing down, and the specter of civil war remains a real possibility.

Sudan, of course, is one of Israel’s new Arab partners under the Abraham Accords. Where does this chaotic state of affairs leave its normalization deal with Israel?

Shortly after the overthrow of the Bashir regime in April 2019, a series of contacts and talks began between Khartoum and Jerusalem involving in-depth US and Emirati mediation. Burhan and his military supporters wanted to distance themselves from the old Bashir regime, which had hosted Hamas and Islamic jihad, and allowed Sudan to become an open conduit for weapons and supplies passing to the Gaza Strip. With a new regional order emerging, predicated on opposition to Iran and a working partnership with Israel, they seized on the chance to join.

It was in February 2020 that Israel’s then-prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, met Burhan, head of the Sovereignty Council of Sudan, in Uganda, where they agreed to normalize the ties between the two countries. An initial agreement on October 23, 2020 saw Sudan removed from the US government list of countries promoting terrorism, and on January 6, 2021 in a quiet ceremony #in Khartoum, Sudan formally signed up to the Abraham Accords.

Just how substantive is the Israel-Sudan normalization deal? Hamdok’s departure does not alter the basic situation, acknowledged by Birhan (whatever his true intentions): Sudan is a nation in transition, on the road to parliamentary elections scheduled for July 2023 and intended to usher in full democratic civilian rule.